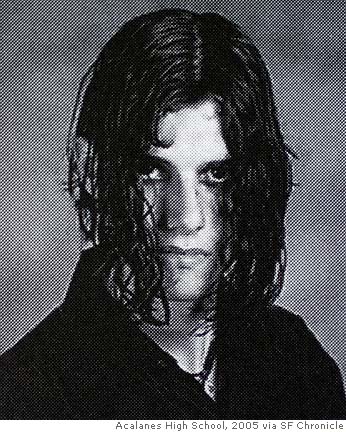

Prosecutor: Scott Dyleski’s vicious slaying of neighbor ‘wasn’t Goth … it was murder’:

MARTINEZ, Calif. — Gothic imagery, dark poetry and an obseassion with cult murders imbued the mind of a 17-year-old former Boy Scout who is accused of brutally killing 52-year-old Pamela Vitale, prosecutors said during opening statements Thursday in the teen’s first-degree murder trial.

“It wasn’t Goth, it wasn’t even death, it was murder,” prosecutor Harold Jewett said of the nature of writings and drawings that investigators found in a search of the boy’s bedroom.

Oh, hell. They are using the “Judas Priest” prosecution strategy.

The defendant, Scott Dyleski, has pleaded not guilty to the murder of Vitale, a mother of two and former Bay Area high-tech executive who was married to prominent California defense attorney Daniel Horowitz.

Dyleski is also charged with the special circumstance of murder during a burglary.

Dyleski allegedly disguised himself in a black ski mask, gloves and trench coat before entering Vitale’s home and making a surprise attack on his neighbor, shortly after 10 a.m. on Oct. 15, 2005.

“Scott Dyleski is not a killer and he did not commit this crime,” said his attorney, public defender Ellen Leonida, who promised the jury that DNA evidence and an inconsistent timeline will show the boy had nothing to do with Vitale’s murder.

Dyleski had multiple scratches and marks on his body and face when he was examined by police. Dyleski says he received them during a nature walk.

Isn’t that convenient?

A member of Dyleski’s household will testify, according to Leonida, that the time was 9:26 a.m. — before Vitale’s death — when the teen returned from his walk.

Leonida tried to bring Dyleski’s gentle qualities to the forefront. She described him as a kind kid, a helpful babysitter, a former little leaguer and Frisbee team member. He may have enjoyed dark music and dress, Leonida told jurors, but he cared deeply for life, and was so harmless that he didn’t eat meat or wear leather.

In my opinion, from the descriptions, I’ve heard members of Dyleski’s “household” are not exactly what I would call trustworthy. And so what if Dyleski is a vegan/vegetarian. That does not exclude him from murder. Hell, most animal rights activists care more for animals than they do for people.

Prosecutor Jewett portrayed the teen as a ruthless killer who stunned and attacked Vitale, leaving her with “26 separate devastating wounds to the head,” dislodged teeth, broken fingers.

“She fought as valiantly as she could, but the attack continued,” Jewett said.

Internal bleeding in Vitale’s brain led to her immediate death, Jewett said, but even after she died from her head injuries, the attack continued.

Vitale was stabbed so viciously in her abdomen, Jewett said, that her intestines were exposed. And then the killer carved a symbol into her back.

“Mr. Dyleski was big into symbols. He signs his name and puts his symbol on his artwork,” Jewett said.

The prosecutor drew a symbol on a white piece of butcher paper that represented the signature Dyleski allegedly carved into Vitale’s back, an H-shaped symbol with an extended T-bar.

Jewett told the jury that he planned to call some 40 witnesses, including Dyleski’s best friend, who tipped off police to the pair’s marijuana-growing scheme that allegedly was the impetus for Dyleski’s run-in with Vitale; the defendant’s girlfriend, whom he allegedly asked to keep a red backpack filled with evidence; and his own mother, a reluctant witness who agreed to cooperate in exchange for escaping prosecution herself after she destroyed clothes, notes and other evidence.

Prosecutors also plan to offer the jury about 100 exhibits, including DNA evidence, bloody clothing, footprints, glove prints, fingerprints, and journal writings and drawings found in Dyleski’s room.

“Listen carefully, in particular to the DNA evidence,” Leonida told jurors, alleging that a third DNA profile was found at the crime scene.

“Scott Dyleski had no motive whatsoever to commit this crime,” Leonida said.

The evidence sounds pretty overwhelming to me. I just hope the prosecution doesn’t screw it up by overplaying the “goth” card.